A Conversation with Charles Burnett (KILLER OF SHEEP)

Imagine this peculiar back-and-forth as mere embellishment. There is a far superior interview—in Interview, no less—with the great Charles Burnett and Barry Jenkins “You’re Either a Storyteller or a Liar” Go read that. Then, if interest persists, you can return for more of the same (only lesser).

[Granted, if you haven’t seen the film yet, do that before you do anything else!]

Unfortunately, for those only arriving at Killer of Sheep now, not quite a half-century later, its well-deserved reputation precedes it. The film is understandably accepted as one of the greatest of American independent films. For years, though, it was either unseen or under-seen (due to issues with music rights, a common affliction of independently-produced works throughout the post-1927 history of filmmaking—see also Two Lane Blacktop—or other distribution woes, such as Eagle Pennell’s The Whole Shootin’ Match, a similarly grand same-time-period series of vignettes in black-and-white which serves as an honest profile of ordinary individuals far too rarely seen on screen). Any discussion of …Sheep’s ample merits places too much pre-awareness on the audience for this genuinely understated exploration of life in an otherwise under-documented corner of late-1970s Los Angeles suburbia. Initial ignorance, in this instance (as in many), enhances an appreciation. If you must, though, read on.

Hammer to Nail: In a lifetime of impractical decisions, this is another. The very moment that we are finished speaking, I have to disappear for the airport. I did not want to pass-up the opportunity to speak with you! This is the time that we have. For decades, I have been recommending Killer of Sheep to anyone who would tolerate me pestering them about seeking it out. Additionally, I’ve known Amy [Heller] and Dennis [Doros] at Milestone Films for many years and I could not resist any moment to promote a great film, of course, along with their admirable distribution of your work (along with Ross Lipman’s restoration). Returning to the very beginning, it seems essential to delve into your time at UCLA and the formation of the L.A. Rebellion.

Charles Burnett: First of all, L.A. Rebellion was a name-tag that [film scholar] Clyde Taylor and Teshome Gabriel, a teacher of film and social change, created. Clyde Taylor was a critic and he taught at UCLA. He was always in the background, commenting on the films that we were making. Later on, the students of color at UCLA were trying to make films about their participation in the community. There was no model for what we were supposed to do as filmmakers except for films by Oscar Micheaux and others which we did not have the opportunity to see until later in life.

It wasn’t until Taylor and Willie Bell, a student at UCLA, recommended the films of Oscar Micheaux at a festival where these films should be shown. That was the first time I’d seen anything by Micheaux! We were consciously aware of people who were seriously about filmmaking. We were trying to find a solution for what was going on and the problems in the neighborhood. There was also the kind of narrative that Hollywood was continually perpetuating, from Birth of a Nation and after. We had to deal with the legacy of that. When Taylor came in, as one of the first black teachers in the UCLA film department, he brought international films. That is where we learned about what films could possibly be. People who had a political consciousness and were trying to do something. We talked seriously about making films that spoke the truth. We found examples in the films of Roberto Rossellini and [Vittorio] De Sica…

HtN: Italian neorealism.

Charles Burnett: Neorealism, yes. As well as [Satyajit] Ray and his films. Latin American films. Then there was this really exceptional film, [Michael Roemer and Robert Young’s] Nothing But a Man with Ivan Dixon.

HtN: A fantastic film.

Charles Burnett: It is a fantastic film. We debated that for the longest time. How does Nothing But a Man represent the black community and so forth? It was on a shelf all by itself. We were trying to find our voice. I looked at films that were good and were very sympathetic to what we were trying to do. Those are the films that we gravitated toward. Then, years later, the whole notion of the L.A. Rebellion came about. Some of us looked at it strangely because it was sort of a novelty to us. We knew what we were doing at the time, trying to make films that spoke directly to the needs of the black community.

Filmmaker Charles Burnett

To try to make films that we could share with everyone else about who we were as people. It was a great time because we spent hours in cafes, almost like the French in many ways. Spending time in cafes and the restaurants until late at night. We’d go down from the UCLA campus into Westwood or some place where we could stay until they closed and kicked us out. It was a good time to try to learn about film. UCLA was very great in the sense that you had to work on other people’s films. They encouraged it. It allowed you to do what you want. They had all the equipment there—sound stages and so forth—and we could spend all night there. We did, sometimes! It was great being a film student at that time.

HtN: It was an immensely collaborative atmosphere. I spent some time with Billy Woodberry at the Flaherty Film Seminar a few years back [2016, the year David Pendleton was the programmer]. We talked a bit about the work that you two did together. Obviously, you were the screenwriter of his first feature-length [Bless Their Little Hearts]. It seems like such a vibrant time in filmmaking. There is a lack of the same thing happening at this moment. Filmmakers could use what you were doing while you were at UCLA as a real example for how to get films made on relatively low-budget.

Charles Burnett: I was at the Flaherty Seminars twice [in 1979 and 2004]. That was really delightful because I had started [as a filmmaker] wanting to make documentary films. Basil Wright was one of my teachers at UCLA and he had introduced me to the works of Joris Ivens and [Robert] Flaherty and all of these folks. They’d had the end of the quarter screenings of all the best student films at Royce Hall. I couldn’t make those films. These were personal films about young kids exploring their sexuality or freedom or whatever. I came from Watts. That wasn’t my issue. Mine was just trying to survive on the streets of South Central [Los Angeles] without getting harassed by the police.

There were a lot of incidents where kids would go to jail and get beat up. The police would say, “Well, he fell down the stairs.” There was a major police station there in the heart of Watts. When the kids would get arrested, they’d come out all beat up with arms broken or a bloody head. If you passed the 77th precinct, it was only one story. Where are these stairs? What stairs are they talking about? These obvious lies and things that you are aware of. Then, when I went to UCLA, it was a whole different ball game altogether. You saw how privileged people were at UCLA. That was one of the things that shocked me. That was an eye-opener.

HtN: There was a disparity between many of your fellow students and the filmmakers with whom you were collaborating?

Charles Burnett: It was a disparity between the police at UCLA and the ones in Watts. If you had one seed of weed in the seam of your clothes, the police would come and do a forensic search of everything and call you all kinds of names. If they found anything on you, you were going to jail for a long period of time. It wasn’t overnight or anything like that. UCLA was a great school and the teachers were great but I remember the kids would smoke—not all of them, some of them—and the smoke would come through the vents. There would be no concern about it at all. The police in the physical building would walk through the second floor and ignore the stuff coming out the vents. I would be looking out of the lock, out of the editing room. They just wouldn’t even be aware of it.

HtN: A whole other world.

Charles Burnett: A different world. Many of us who came to know that the school was great about accepting us in many ways. We knew that kids of color had feature-length scripts. They came really wanting to make a film and didn’t know where it was going to go because there wasn’t any kind of distribution for black independent films. You have documentary films or industrial films you could do and, with those, you could find a job. You were in the studios for years and years and years and to be a first camera, you had fifteen years of waiting to get into the union. It didn’t worry us a bit. I didn’t think that I was going to be making films for Hollywood or anything like that. I knew that I was going to be making films as a hobby and shooting on the weekends. I was going to show the community. That was as far as I went and that is why Killer of Sheep took so long to get released because I didn’t have the rights to the music. Unfortunately, I didn’t know Dennis [Doros] and Amy [Heller] then. It wasn’t until many years later. Great people, by the way!

HtN: Given your interest in nonfiction filmmaking, how did you assemble the vignettes that became Killer of Sheep? You gathered the actors, you were shooting every weekend, as you’d mentioned. How did you make that choice? You had completed a handful of short films earlier [Several Friends and The Horse] but, for your first feature-length work, how did you arrive at this series of stories involving this particular [fictional] family?

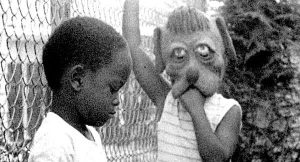

A still from KILLER OF SHEEP

Charles Burnett: I wanted to do something that really showed what it was like. What the people were like, people that I admired and respected. I grew up in a community where everyone was from the south, basically. Hardworking people. I wanted to honor them in a way. I wanted to make a film about them and the things that were not seen in entertaining films, as such. The films Hollywood made. I went to movies all the time. I liked them but they weren’t anything I could really relate to, except for a few of them. I wanted to talk about the men and women and the kids that I grew up with and what you would see if you came to South Central. This is what you would see. How can you improve upon it? It wouldn’t be from my perspective, in a sense. It would be how you, looking at this film, make changes in society or look for answers to the problems you see in the faces of these people.

I thought I would be really honest because I was there when the Watts riots happened. When I had hair, I’d go down to the south to get my hair cut. These older gentlemen from the south would argue and talk about things. I was a fan of Paul Robeson. They weren’t. They were very patriotic, they’d been to the war. They didn’t want people to talk badly about this country. They looked down on Paul Robeson because he had mentioned the problems of living in America. They were not very sympathetic toward him. I was a young radical, so to speak, and I’d celebrate his birthday. They said, “Look, if you buy a ticket to Russia, promise not to come back.” If you looked at Watts, it was a really decent place. It was a really a fun place to be. They had a poor working class but they kept their houses clean. They bought houses for the first time. They were property-centered. They were really trying to get their kids in school. They brought a lot of the values from a working class south into South Central.

I had to go to church every Sunday, before I could go to the movies, I had to go to Sunday school first. There were principles and things that we had to abide by. Church was a big, phenomenal part of your life. I wanted to include all of that. It was very complicated. When we get older, they expect us to have answers. You would always ask if you know what you would do? How would you make it better? Being filmed in social change, that was the edict. Films that were going to make positive changes in society, in local communities. The reason I respect a lot of the older people was because men would run into you on the street and they’d say, “Boy, stay in school and you get a diploma.” They had the kind of parents who tell the kids to become lawyers. Funny thing was it happened every day when I was growing up.

HtN: From the consecutive weekends, which were among the memorable moments while you were filming?

Charles Burnett:: For one scene, the dog—a big German Shepherd—needed to chase but he wouldn’t do it this time. He wouldn’t. We had to come back but this kid in the Navy lived in the same house. He had this little dog that he said, “My dog would do it.” I didn’t want to do it because the dog was too small. I couldn’t get the other dog to do it. I said, “Okay, we’ll use your dog.” The kids would ride by and the dog would try to attack them. I think a big dog would’ve been better. It would’ve seemed more threatening and the sell would’ve been better. Anyway, I was happy to get the scene at all.

HtN The scenes of the children playing persistently expresses that. Would you primarily set-up those situation and film the results? How do you manage a group of kids immersed in some sort of controlled-chaos situation?

Charles Burnett: It was chaos. You learn. I remember, luckily, two things. One, the kids and the fighting. Fighting in the alley. Very natural, in a sense, because girls and boys the same age don’t get along. The girls like older boys and the boys like older girls. But they don’t like kids, the boys and girls their own age. This was automatic. A water-and-oil kind of a thing. You don’t mix them! It was easy for them to be hostile toward each other. You didn’t have to do much. Later, what I learned was my niece [Angela Burnett], in the scene in the kitchen where there is an antagonistic relationship between her and her mother [Kaycee Moore] and the father [Henry Sanders]. The father, Stan, does everything she wants and the mother is jealous. The kid is supposed to get a glass of water and look very frustrated at her mother. I was telling her, “Go in, get a glass of water from the faucet.” I kept getting lower and lower, to her level. She’s down to my waist. I kept getting further and further down and I’m telling her, “You drink the water like this, you look at your mother and then you do this and that.” This goes on for a while. I noticed that when I was trying to get down to her level, she was thinking that I was telling her to get lower and lower. Then it dawned on me. She was reacting to what I was doing, which was the wrong thing. I was trying to get down to her level. After that, I just told her what her motivation would be and what she was supposed to be thinking. Just like that, the kid would just do it. Smart like that. It was the older ones who’d lost all of those brain cells. It made it difficult!

HtN: The final detail I wanted to ask before I venture off for a flight is about the reissue of The Annihilation of Fish. For many years, it was a film about which I’d merely read. How has the experience been for you, now that you have that film in re-release along with this new restoration of Killer of Sheep? Ideally, this synchronistic pairing will encourage viewers to revisit your other films as well.

Charles Burnett: I hope so. I think it has been great. I have to give credit to the people who’ve helped to bring it back out and all of things that made it possible. I was very sad about the fact that James Earl Jones, Margot Kidder, Linden Chiles and so forth didn’t get the exposure that they deserved [when it initially premiered]. It could have happened right when we screened at Toronto. It took all of this time because of the bad reviews and all of this criticism of the film. I don’t mind people having problems with the films that I’ve made. You can’t make a film that everyone is going to like. That is part of the nature of making a film. It will get criticism, whatever kind. But I was mad at the fact that much of it was unnecessary. People liked the film every time we screened it. The audience was positive and so forth. I object to why critics were particularly cruel about it.

HtN: They were obviously wrong because the response, now that The Annihilation of Fish has returned, is exactly the opposite!

– Jonathan Marlow, Executive Director | SV ARCHIVE [SCARECROW VIDEO]